Last Updated on by Mitch Rezman

First, a little semantic housekeeping in these modern times of ornithology. The term beak & bill can be used interchangeably – or so I’m told.

Our new economical bird nail trimmer has become very popular once pet bird keepers realized how easy it was to trim their own birds nails while saving money at the same time.

From time to time we do have people asking about trimming their bird beaks because they appear to be a little too long or may exhibit a “bump”.

Although we recommend using one of our electric nail trimmers to keep your bird’s nails trimmed neatly we do not recommend that you attempt to trim your bird’s beak yourself.

It’s a sensitive organ and has a lot of sensory receptors, which could potentially be very painful to your bird if handled the wrong way. Which got me started on today’s topic.

BTW – we recommend having this done by a veterinarian who may need to grind or cut an overgrowth or deformity thereby allowing the bird to eat and preen normally.

I thought it was interesting to learn while researching this subject that apparently it’s done routinely to farm poultry, particularly egg-laying chickens. It’s called debeaking and it is done to the flocks so they don’t inflict pain upon one another.

Usually with a cauterizing blade or infrared beam which cuts off about half the upper beak and a third of the lower beak – and yes it hurts the birds but they recover and they’re found to be less stressed given the highly stressful situation they live in.

Your bird’s beak is the most important part of his or her anatomy. They use it for any number of things from grooming to eating to moving objects around. Fighting, probing for food, courtship, feeding youngsters, and for some species, even killing prey in the wild.

Stepping back for a moment, we’ve been talking about bones and feathers a lot recently. Before we jump in, I think it’s important to note that beaks are another evolutionary trade-off for weight coming in much lighter than jaws and teeth.

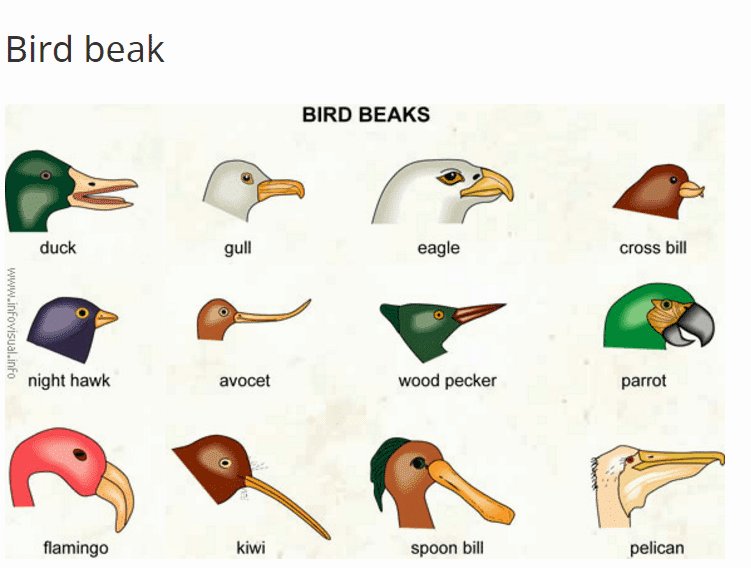

You can see from the illustration below, beaks vary widely based upon species’ needs, but at the end of the day all beaks are very similar. They all have an upper and lower mandible which are both covered with a thin layer of the keratinized epidermis (the same structural proteins found in human hair and nails) known as the rhamphotheca.

Besides parrots, owls, raptors, turkeys, and curassows have a waxy structure called a cere which covers the base of their bill and usually contains the nares (a bird’s nose or entry to the respiratory system).

Once in a while, you’ll see some feathers covering the cere but usually, it’s bare yet brightly colored. In Raptors, the cere produces a sexual signal which can say “I’m hot stuff” – or not.

The upper mandible gets support from a three-pronged bone called the intermaxillary. This design where the upper prong of the bone is embedded into the forehead while the two lower prongs attached to the sides of the skull make for a very efficient operation.

At the base of the upper part of the beak, you’ll find a thin sheet of nasal bones that are attached to the skull and is something called the nasofrontal hinge which enables up and down motions.

The lower mandible is supported by a single bone called the inferior (lower) maxillary bone which is a compound bone made of two pieces that attach on either side of the head to the quadrate bone.

Muscles that enable the bird to close its beak are attached to both sides of the head. In most birds, the muscles that press the lower mandible are weak and relatively small when you compare them to the jaw muscles of similarly sized mammals.

What you see on the outside of the beak is a thin horny sheath of keratin (rhamphotheca) which comes in two flavors depending upon whether it’s on the top or the bottom part of the beak. There’s an avascular layer which means blood runs through it. Beaks grow continuously (in most species) because of it.

It is said that something called the “bill tip organ” is far more well-developed among foraging species of birds like parrots and birds from wet habitats. This bill tip end has a high density of nerve endings known as the corpuscles of Herbst.

There you’ll find very tiny pits in the bill’s surface which are occupied by cells that sense pressure changes. It is thought that this allows birds to have a remote touch which means it can detect movement without direct touch.

If you have ever had a finger chomped on by a large parrot the two cuts were made with the edges of the top and the bottom of the beak and these are called tomias. The ridgeline of the upper part of the beak is called the culmen – one area measured when banding birds in the wild.

Much like feathers, birds have various color banks resulting from concentrations of pigments. We know that birds can see light in the ultraviolet spectrum which may radiate from some of their beaks once again signaling to other birds and about their “quality”.

Some Toucans use their beaks (the walls of which are hollow) to rid themselves of excess body heat.

Let’s not forget the egg tooth which is not really a tooth but a calcified projection on a full term chicks beak which they use to chip their way out of the egg. Most chicks lose their egg tooth within a few days of hatching.

A problem with hand-fed young birds or chicks is when human hands are too strong and not holding the beak properly during feeding, the beak may grow incorrectly as the chick matures which results in a deformity. In Macaw chicks the use of too much force can cause the top beak to go off to one side. The beak is then called “scissored”.

With young cockatoos, cockatoo moms pull on the upper beak of the young birds as she clamps her beak and feeds with a pumping action. By not pulling the beak during the feeding process the result may be the upper beak being too short in relation to the lower one.

Written by Mitch Rezman

Approved by Catherine Tobsing

Author Profile

Latest entries

Feeding Exotic BirdsDecember 29, 2025How to Switch or Convert Your Bird From Seeds to Pellets: Real-Life Case Studies and Practical Guidance

Feeding Exotic BirdsDecember 29, 2025How to Switch or Convert Your Bird From Seeds to Pellets: Real-Life Case Studies and Practical Guidance Feeding Exotic BirdsDecember 16, 2025A Practical, Budget-Smart Guide to Feeding Birds Well

Feeding Exotic BirdsDecember 16, 2025A Practical, Budget-Smart Guide to Feeding Birds Well Bird EnviornmentsDecember 7, 2025Understanding Budgie Cage Bar Orientation: Myths, Realities & Practical Solutions for Vertical-Bar Bird Cages

Bird EnviornmentsDecember 7, 2025Understanding Budgie Cage Bar Orientation: Myths, Realities & Practical Solutions for Vertical-Bar Bird Cages Feeding Exotic BirdsDecember 5, 2025How Dr. T.J. Lafeber Rewrote the Future of Pet Bird Nutrition

Feeding Exotic BirdsDecember 5, 2025How Dr. T.J. Lafeber Rewrote the Future of Pet Bird Nutrition