The Ultimate List of 13 Bird Beak and Foot Structures

Last Updated on by Mitch Rezman

Factoid – beaks are an evolutionary concession to drop weight which is why birds don’t have jaws & teeth.

Finches use their beaks like tweezers for extracting seeds.

Parrots use their hookbill beaks to crack open nuts and hard-skinned fruit.

Woodpeckers, well they just are capable of breaking down almost any tree.

Our economical bird rotary nail trimmer has become very popular when people realize how easy it is to trim their own bird’s nails while saving money at the same time.

Although we recommend using one of our electric nail trimmers to keep your bird’s nails trimmed neatly we do not recommend that you attempt to trim your bird’s beak.

It’s a sensitive organ and has a lot of sensory receptors and which could potentially be very painful to your bird if handled in the wrong way, which got me to thinking about today’s topic.

Your bird’s beak is the most important part of his or her anatomy.

They use it for any number of things from grooming to eating to moving objects around.

Fighting, probing for food, courtship, feeding youngsters, and for some species even killing prey in the wild.

You can see from the illustrations below, beaks vary widely based upon the specific needs, but at the end of the day all beaks are very similar.

[Best_Wordpress_Gallery id=”17″ gal_title=”Bird Beaks”]

They all have an upper and lower mandible which are both covered with a thin layer of keratinized epidermis known as the rhamphotheca.

Last but not least you’ll usually find two holes known as nares which serve as the bird’s nose or entry to the respiratory system.

A little semantic housekeeping here in these modern times of ornithology.

The terms beak & bill can be used interchangeably.

The upper mandible gets support from a three-pronged bone called the intermaxillary.

This design where the upper prong of the bone is embedded into the forehead and the lower prawns are attached to the sides of the skull makes for very efficient operation.

At the base of the upper part of the beak, you’ll find a thin sheet of nasal bones that are attached the skull is something called the nasofrontal hinge which provides mobility.

A problem with hand-fed young birds or chicks is when human hands are too strong and or not holding the beak correctly the beak can grow incorrectly as the chick matures which results in a deformity.

In Macaw chicks the use of too much force can cause the beak to go off inside as well.

With young cockatoos, cockatoo moms pull on the upper beak of the young birds as she lifts her beak and feeds with a pumping action.

By not making that pulling of the beak the feeding process can result in the upper beak being too short in relation to the lower one

The lower mandible is supported by a single bone called the inferior maxillary bone which is a compound bone made of two pieces that attach on either side of the head to the quadrate bone.

Muscles that enable the bird to close its beak are attached to both sides of the head.

What you see on the outside of the beak is this sheath of keratin. The rhamphotheca comes in two styles depending upon whether it’s on the top or the bottom part of the beak.

There’s also a vascular layer which means blood runs through it and it grows continuously in most bird species

It is said that something called the bill tip organ is far more well-developed among wet habitat birds including parrots.

This bill tip end has a high density of nerve endings known as the corpuscles of Herbst.

There you’ll find very tiny pits in the bill surface which are occupied by cells that sense pressure changes.

It is thought that this allows birds to have a remote touch which means it can detect movement without direct touch.

If you’ve ever had a finger chomped on by a large parrot the two cuts were made with the edges of the top and the bottom of the beak and these are called tomias.

The ridgeline of the upper part of the beak is called the Culmen – one area used to measure pending birds in the wild.

Much like feathers birds have various color banks resulting from concentrations of pigments.

We know that words can see light in the ultraviolet spectrum which may radiate from some of their beaks once again signaling to other birds and about their quality.

Some Toucans use their beaks (the walls of which are hollow) to rid themselves of excess heat.

Let’s not forget the egg tooth which is not really a tooth but a calcify projection on a full-time six peak which they use to chip their way out of the egg.

Lately, I’ve been criticized, accused of being self-righteous, and generally dissed by caged bird keepers who feel clipping bird’s wings is the right thing to do.

Segway to bird and parrot feet

So I proudly wear my Scarlet (Macaw) letter “F” (for flight) on my chest.

But I think I’ve done, actually, Denise has done a fair job of stating the benefits of wing clipping. And while the fight between the Hardfeathers and the Macaws rages on I like to bring some clarity to the situation.

I want to make something very clear.

Our corporate mission is to be an advocate for the birds. We want to make sure your bird is healthy whether its wings are clipped or not.

I’d like to move from the debate for a moment and bring some clarity to the subject of caged bird care for bird to have clipped wings.

If a bird’s wings are clipped, it’s grounded. It basically doesn’t fly.

That means your bird is on its feet literally 24/7 – Which begs the question, “When was the last time you closely examined your bird’s feet?”

So if I have a little fun exploring things you might not know about your bird’s feet.

There are several categories of bird feet including webbed and unwebbed.

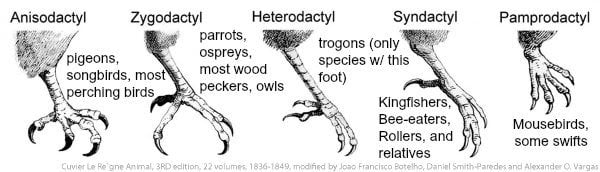

The five most common of bird’s feet are classified as anisodactyl, zygodactyl, heterodactyl, syndactyl, pamprodactyl.

For this discussion we will focus on zygodactyl (Greek ζυγον, a yoke) – two toes in front (2, 3) and two in back (1, 4) – the outermost front toe (4) is reversed.

Editors note Woodpeckers when climbing can rotate the outer rear digit (4) to the side in an ectrodactyly arrangement.

Many birds that perch like woodpeckers, owls, cockatoos, ospreys, and most parrots, have zygodactyl feet.

Interestingly woodpeckers can rotate the outerwear digit (4) to the side creating an ectropodactyl arrangement.

Owls, osprey, and turacos can rotate the outer toe (4) back and forth.

Editors note: Zygodactyl tracks have been found dating to 120–110 Ma (early Cretaceous), 50 million years before the first identified zygodactyl fossils.

Avian syndactyl is like anisodactyl but where the forward-pointing toe and the outer toe ports like soldering three toes together.

Heterodactyl is like zygodactyl, except that digits 3 and 4 point forward and digits 1 and 2 points backward.

Feathered factoid: The tarsometatarsus is a bone that is only found in the lower legs of birds and certain non-avian dinosaurs.

All four toes on a pamprodactyl foot face front. Most swifts have pamprodactyl feet where digits one and four easily move forward and backward.

When all toes are rotated forward, birds like swifts can use their small feet as hooks.

This enables them to easily roost on the walls of different materials both domestic like chimneys (think chimney swifts) and natural as well as tree hollows.

Written by Mitch Rezman

Approved by Catherine Tobsing

Your zygodactyl footnote

Author Profile

Latest entries

The Traveling BirdJune 26, 2025Can You Name 5 Parrot Species That Are Living Wild in the USA?

The Traveling BirdJune 26, 2025Can You Name 5 Parrot Species That Are Living Wild in the USA? Bird BehaviorJune 26, 2025How is it Parrots Are Problem Solvers Social Animals and Even Use Tools?

Bird BehaviorJune 26, 2025How is it Parrots Are Problem Solvers Social Animals and Even Use Tools? Bird & Parrot AnatomyJune 25, 2025How a Tiny Chemical Modification Makes Parrots Nature’s Living Paintings

Bird & Parrot AnatomyJune 25, 2025How a Tiny Chemical Modification Makes Parrots Nature’s Living Paintings PigeonsJune 20, 2025How Do Parrots Thrive in Cities Outside Their Native Habitats?

PigeonsJune 20, 2025How Do Parrots Thrive in Cities Outside Their Native Habitats?