Last Updated on by Mitch Rezman

Hello All

And thanks for your contributions to this often difficult topic.

Yes, it is true that flighted birds may have accidents, which some folks may attribute to their being flighted.

But then birds whose flight has been impaired also have accidents due to flight impairment.

Clipped birds are vulnerable to death during escape from cats, dogs and being run down by vehicles.

We have several stories of such incidents in the UK, and these will continue to happen.

Flighted birds are not so vulnerable to *these* risks.

So, ALL birds are subject to risks in the home, whether they are flighted or not: clipped birds are just subjected to *different* risks than those of flighted birds.

Generally, wing-clipping is done for owner-convenience, rather than bird ‘welfare’.

After nearly 20 years of keeping parrots, and with a good understanding of avian biology and evolution, I came to the conclusion that if birds are to be kept in captivity, then they have to be kept as the flying creatures they are.

I can’t go into the full case for this here.

But after 175 million years of evolution of flight, the birds need to retain their main means of getting about, is fundamental to their biology and behavioral repertoire.

Since parrots are not domesticated creatures, but still essentially ‘wild’ (even captive-bred ones) then I feel our default stance should be that we should adapt our homes to the birds’ needs, rather than adapt the birds’ anatomy by removing their most vital bits.

I don’t think it’s about having them back in the rain forest, since, with captive birds, that’s never going to happen.

The issue is about ensuring *captive* birds have what they are adapted to have, and that means daily flight. In one of my talks (in Minneapolis last year)

I asked a large audience of parrot keepers (most of whom kept clipped birds) if any of them could answer the following questions:

A. Could anyone describe the molt sequence (first to last flight feathers to be shed and replaced) in any bird?

B. Could anyone tell me the rate of feather growth in parrots; i.e. growth per 24 hours of flight feathers?

C. Did anyone feel they had a good understanding of flight in birds; i.e. how they generate lift, hover, stall, brake accelerate, decelerate, and change direction, etc?

D. Could anyone describe the innate escape reflex action which all flying birds use?

No-one could answer the first 3 Q’s, but some had a go at ‘D’. I felt that to clip birds (or to have clipped birds) and not know these things, is a bit like being a car mechanic and not knowing the difference between a brake hose and a fuel line (pretty basic stuff when you come to fix cars).

Sadly, this is ‘where we are at’ with parrots at present.

Most folks who have them do *care* about them, but they know very little about how birds developed into the fantastic creatures they are.

One of the problems of removing any feathers (a so-called ‘light clip’) is that birds use their wings, and indeed whole body, in a slightly different way to that used in fixed-wing aircraft.

When a bird is accelerating, it uses its whole body and its entire wing surface to do this.

When it is doing the opposite (braking) it does the same; it uses its whole body/wings and tail to do the *opposite* action (forms a sort of ‘parachute’ shape, and uses its primaries to generate reverse thrust.

If you clip these primaries, the bird’s whole range of flying abilities is impaired.

It cannot accelerate, brake, turn, or hover as well as if it had all its feathers.

So, a clipped bird risks having to land (or crash land) at *higher speeds* than full-winged birds.

‘Control’ of flying birds is easily affected by basic flight commands.

These include: Fly off me; Fly to me; Do *not* fly to me, and leave your present place and fly to another place, but not to me.

Once you have these commands taught, you have good ‘control’ of flying birds.

I often have 4 or five birds all-out flying around together. But I can only do this because they are all trained in-flight commands.

Many ‘accidents’ which befall flying birds, and are used to illustrate the case for wing-clipping, involve birds who have poor flight skills. I.e. birds who were previously or recently clipped.

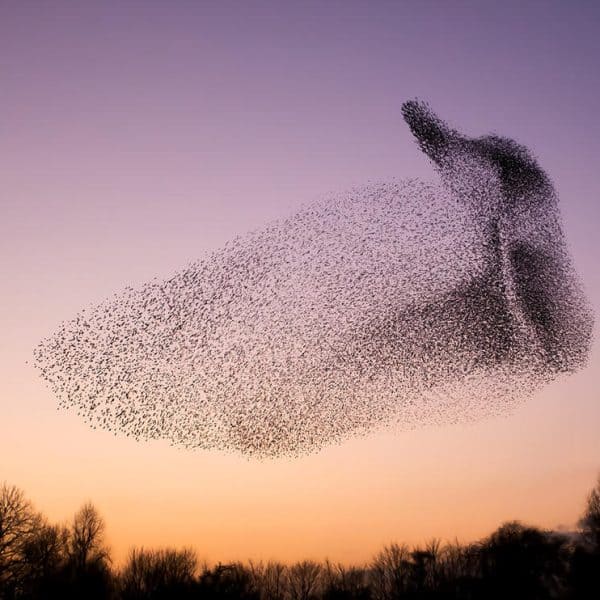

Birds that are never clipped and are encouraged to fly, do so with a degree of skill (and speed) which is difficult for the human eye to follow.

This is a key aspect of the beauty of birds. They leave us standing, and they are meant to do so.

Author Profile

Latest entries

The Traveling BirdJune 26, 2025Can You Name 5 Parrot Species That Are Living Wild in the USA?

The Traveling BirdJune 26, 2025Can You Name 5 Parrot Species That Are Living Wild in the USA? Bird BehaviorJune 26, 2025How is it Parrots Are Problem Solvers Social Animals and Even Use Tools?

Bird BehaviorJune 26, 2025How is it Parrots Are Problem Solvers Social Animals and Even Use Tools? Bird & Parrot AnatomyJune 25, 2025How a Tiny Chemical Modification Makes Parrots Nature’s Living Paintings

Bird & Parrot AnatomyJune 25, 2025How a Tiny Chemical Modification Makes Parrots Nature’s Living Paintings PigeonsJune 20, 2025How Do Parrots Thrive in Cities Outside Their Native Habitats?

PigeonsJune 20, 2025How Do Parrots Thrive in Cities Outside Their Native Habitats?

Chrischan

1 Oct 2017I had my flighted conure on my shoulder and he was startled by a hawk trying to flush it off my shoulder, just 8 feet from my door. He was picked up in the air by the hawk and was flown away, screaming. Never again.

Nora Caterino

3 Oct 2017I’ve talked to Greg Glendell personally and while he feels strongly about flighted birds and free flying, I disagree with him strongly. Hawks, ospreys and eagles inhabit where I live and any of these can capture and eat my dear Timmy. Also, my apartment is not huge and he would be able to get into too many things — like flying into the kitchen and landing on a hot stove eye or hot pan. I do a very light clip on him so that he can fly level and land gently but can’t gain altitude. When we are outdoors in an area where predators from the air are prevalent, I have him sit on my finger and hold his toes. He thinks it’s kind of neat and does not object. I also use this technique when getting up or sitting down with him, when walking on a windy day when he might fly level into the street easily. I truly respect Greg’s techniques and they work for him but I am simply not willing to take the risk of free flying or full flight. Too many horror stories like Chrischan’s sad loss of his conure.