Last Updated on by Mitch Rezman

Anatomy and function

The upper respiratory system (URS) consists of the external nares, operculum, nasal concha, infraorbital sinus, and choanal slit.

The nares are paired symmetrical openings with an operculum within each. The nares each communicate with the nasal cavity containing the concha.

The left and right nasal cavities are separated by a septum. The nasal cavity communicates with the left and right infraorbital sinus.

This sinus has five diverticula that extend into the skull (cranial, ventral, and medial to the eye) and mandible. The lateral margin is skin and subcutaneous tissue (not bone). The convoluted nature of the sinus makes URS infections difficult to treat.

The left and right sinus communicate with each other and the air sacs, allowing URS infection to spread to the lower airways. The choanal slit forms a V shape on the roof of the mouth. The choana is surrounded by papilla in most species.

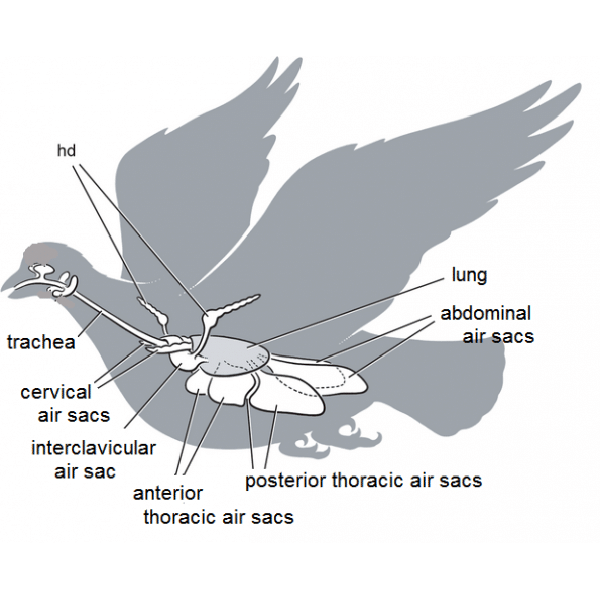

The lower respiratory system (LRS) consists of the laryngeal mound, trachea, lungs and air sacs. The trachea is supported by complete tracheal rings.

The syrinx, or avian vocal organ, is located at the tracheal bifurcation. The trachea divides into two primary bronchi which further divides into four pairs of secondary mesobronchi.

Parabronchi communicate with air capillaries where gaseous exchange takes place. The lung airways communicate with the air sacs.

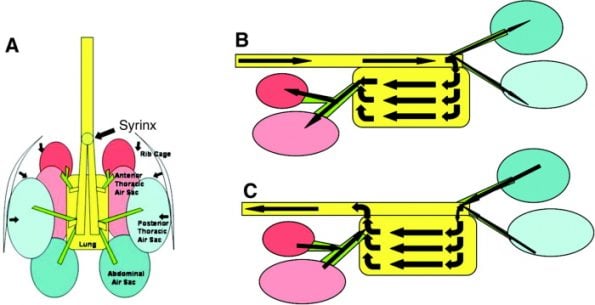

The lungs are in contact with thoracic ribs 1-8, are non-lobed, and do not change in volume. In general, the air sacs allow a unidirectional airflow through the lungs, so air is passing through the lungs on both inspiration and expiration.

This system makes avian gas exchange 20% more efficient than the mammalian system. the air sac system is made up of singleclavicular and paired cervical, cranial, caudal thoracic, and abdominal air sacs.

These air sacs communicate with various pneumatic bones including the humerus, vertebrae, and femur. The functions of the air sacs are ventilation, humidification, and thermoregulation.

The respiratory cycle takes two inspirations to complete. The first inspiratory volume of air is split between the abdominal air sacs and the lungs, on expiration, the abdominal air sac gas is pushed into the lungs and the lung air passes into the cranial air sacs.

The next inspiration and expiration allow some of the lung air and the cranial airsac gas to be expelled into the trachea, completing the cycle. The abdominal air sac gas closely resembles the environmental air and this is often used to explain the higher incidence of disease in these air sacs.

Birds do not possess a diaphragm. Respiratory movements are dependent upon the movements of the ribs and sternum. Consequently, handling techniques should not restrict sternal movements.

Clinical Examination of Patient with Respiratory Signs

The bird should be examined within its cage initially and an assessment made of the severity of the respiratory disease.

The marked abdominal effort, open mouthed breathing and cyanosis are signs associated with increased risk with handling and so oxygen therapy and/or placement of an airsac tube may be required to stabilize the patient before further examination.

The patient should be examined in a dimly lit room, and quickly but gently restrained to minimize stress.

The neck, wings, and feet are restrained leaving the chest unrestricted. This can be achieved with one hand in budgies but larger birds require a two-handed approach using a towel.

The towel is used to restrain the wings and is initially placed over the whole animal whilst the neck is located and restrained.

The use of thick gloves is to be avoided as it encourages poor handling – the head does not ‘need’ to be adequately restrained to prevent bites and thick gloves prevent appreciation of the tightness of the grip.

Auscultation using a small (pediatric) stethoscope head should be used to assess the position and severity of the condition. The nares should be examined for signs of erosion or discharge. The choana should be free of discharge. Blunting or edema of the choanal papillae is an indication of chronic change.

Diagnostic Approach

Differentiate between primary respiratory disease and other diseases such as;

- malnutrition, obesity

- goiter

- abdominal fluid; ascites (liver or renal disease, neoplasia), blood (trauma)

- neoplasia

- systemic viral diseases (herpesviruses, paramyxovirus)

- cardiac disease (rare)

Differentiate between URS and LRS disease…

- URS Signs

- rhinorrhoea

- periocular swelling

- coughing, sneezing, voive change, dyspnoea

- LRS Signs

- tail bobbing

- coughing, open mouthed breathing

- easily stressed but lethargic

- depressed

Diagnostic Workup

In all cases to include CBC and biochemistry (Chlamydia tests), whole body readiography, and fecal examination.

- Upper Respiratory System

- examination, palpation, transillumination of URS

- choanal culture (normal flora is Gram-positive)

- sinus flush and culture

- Lower Respiratory System

- auscultaion of lungs and air sac areas

- endoscopy, culture and biopsy

- tracheal / lung wash for culture and cytology

Differential Diagnosis

- Upper Respiratory Tract

- rhinitis

- sinusitis

- vitamin A deficiency

- parasites

- foreign body

- (also reovirus, avian pox, allergy)

- Lower Respiratory Tract

- air sacculitis

- pneumonia

- respiratory abscess, granuloma

- parasites, foreign body, allergy

Diagnostic Techniques

Blood Sampling

From the jugular vein, tarsal vein, or cutaneous ulna/brachial vein. Make fresh blood smear and heparinize the rest.

| ABNORMAL FINDING | DIFFERENTIAL DIAGNOSIS |

| Regenerative (blood loss) anaemia | trauma, parasites, coagulopathy, organic disease |

| Haemolytic anaemia | red blood cell parasites, bacterial septicemia, toxicity, immune-mediated |

| non-regenerative anaemia | chronic disease, hypothyroidism, toxicity, nutritional deficiencies, leukemia |

| Leucocytosis | infection, trauma, toxicity, hemorrhage, neoplasm, leukemia |

| Heterophilia | inflammation, stress response |

| Leucocytosis and heterophilia | chlamydiosis, avian TB, aspergillosis |

| Immature Heterophils | severe inflammatory response |

| Toxic Heterophils | septicemia, toxemia |

| Leukopaenia and heteropaenia | viral disease, overwhelming bacterial disease |

| Lymphocytosis | infections |

| Monocytosis | chlamydiosis, granulomas (bacterial, fungal), massive tissue necrosis |

| Thrombocytopaenia | severe septicaemias, rebound from blood loss |

Radiography

Ventro-dorsal: restrain bird in crucifix position using micropore tape

Lateral: lateral recumbency, legs held back, bird parallel to film

Assess skeletal density, lesions (e.g. fractures), the heart normally lies at the second rib to the fifth rib. The lateral margins of the normal heart and liver in psittacine birds create an hourglass shape (there may be a kink between the two in macaws).

On the VD view, the heart covers much of the lung field, the abdominal air sacs outline the liver.

Heart size at the base should equal about 50% of the width of the coelomic cavity at the level of the fifth thoracic vertebra. Cardiomegaly is rare and associated with; endocarditis (often secondary to pododermatitis), chronic anemia most commonly.

Pericardial effusion shown as a large rounded heart is caused by; chamydiosis, polyomavirus, TB and neoplasia. Microcardia suggests hypovolaemia and is an emergency.

On a good-quality radiograph, the parabronchi can be seen as a honeycomb pattern to the lungs. Pneumonic changes are best appreciated at the caudal edge of the lungs on the VD view.

The air sac walls are not readily visible unless they are inflamed when fine lines may be seen in the lateral view.

| RADIOGRAPHIC CHANGES | DIFFERENTIAL DIAGNOSIS |

| Blotchy pulmonary pattern | parabronchial infiltrates |

| Parabronchi indistinct | exudate, haemorrhage, oedema |

| Pulmonary pattern abnormal/irregular | fungal granuloma, abscess, tumour |

| Air sacculitis | bacterial, fungal, hypovitaminosis A |

| Pulmonary masses | fungal granuloma, abscess |

| Subcutaneous emphysema | trauma to pneumatic bones, infraorbital sinus infection |

| barrel-shaped cranial coelom at full inspiration | air sac disease |

Nebulisation

A 1:10 solution of Tylan in a plant sprayer may be used in the treatment of conjunctivitis or URS disease. The plant sprayers generally do not produce fine enough particles to access the lower air sacs, however.

A proprietary nebulizer may be used and the bird placed into a purpose-built nebulizer cage, a glass tank, or a plastic bag with holes in is placed over a small cage.

Sinus Flush

The patient must be restrained firmly or anaesthetized. A syringe of warmed saline (1-2ml per 100g body weight) is pressed to form a seal against the nares and the volume is slowly infused.

The fluid will flow freely from the choana and out of the mouth. Do not force the fluid in. Flush both sides alternately.

Sinus Aspiration

The mouth is restrained opened. A needle is passed through the skin at the commisure of the mouth towards a point midway between the nares and the eye. The needle must be kept parallel to the head and directed under the zygomatic arch. Avoid puncturing the globe. This technique should first be practiced on cadavers.

Tracheal / Lung Lavage

A sterile catheter is inserted through the glottis into the trachea to the point just cranial to the syrinx.

Sterile saline is introduced (0.5 – 1.0ml per kg bodyweight) and immediately aspirated. Cytology and culture (bacterial/ fungal) may be performed on the sample.

The cytology of normal tracheal or air sac lavage has a low cellular content with few pulmonary macrophages or inflammatory cells.

The abnormal aspirate may contain large numbers of heterophils, pulmonary macrophages, inflammatory cells, bacteria, yeasts, etc.

Endoscopy

The air sac membranes may be examined for vascularity, opacity, exudate, bacterial/ fungal plaques, etc.

Swabs for microbiological culture may be taken from the ostium, air sacs, and lung tissue. Biopsies of the lung and air sacs may be rewarding.

(also see Brian Coles’ notes on laparoscopy).

Air Sac Cannulation

Acute severe dyspnoea caused by tracheal blockage is an avian emergency.

A severely dyspnoeic bird may also be stabilized before treatment by the introduction of an air sac cannula if the dyspnoea is caused by a URS problem.

The bird is anaesthetised and placed in lateral recumbency. The area caudal to the last rib is surgically prepared.

A small skin incision is made just caudal to the last rib and the abdominal muscles dissected.

A sterile endotracheal tube or tubing of appropriate size is inserted into the air sac.

If anesthetized using gaseous anesthesia, the bird may lighten as it breathes room air through the air sac tube.

The anesthetic circuit may now be connected to this tube to maintain anesthesia.

The tube is fixed in place using sutures or glue. An aseptically placed tube may remain patent for 10 days.

The tube should be checked frequently to assess patency whilst the patient relies upon this method of ventilation.

Upper Respiratory Tract Diseases

Common aetiologies and treatment(s):

- foreign body in nasal passages

- Dx: unilateral nasal discharge, radiography, transillumination of beak/nasal sinus

- Tx: culture and sensitivity testing of discharge and appropriate antibiotic, flush infraorbital sinuses

- rhinitis

- Bacterial (Gram negatives, chlamydia, mycoplasmas), fungal (aspergillus). Parenteral antibiotics based on culture and sensitivity, nasal flushes and intranasal antibiotics (use ophthalmic solutions), nebulization.

- sinusitis

- Due to bacteria or mycoplasmas (differentials; chlamydia, aspergillosis, candidiasis). Treatment based on sensitivity, flush out sinuses, infuse antibiotics. Vitamin A therapy. Improve ventilation and correct temperature/humidity of the environment. Doxycycline, enrofloxacin, tylosin are good first-line choices. Or 25mg oxytetracycline + 25mg tylosin per kg i.m. BID or Tylan 50 diluted 1:10 in saline and injected into infected sinus.

- rhinoliths

- Concretions of dust, dirt and nasal mucus blocking external nares, a sequel of chronic sinusitis/ hypovitaminosis A. Remove with a needlepoint, and treat the underlying cause.

- abscesses

- lingual, palatine, periocular, submandibular sites. Abscesses of submandibular salivary gland common in birds fed seeds only, as it undergoes squamous metaplasia associated with hypovitaminosis A. Surgical removal of encapsulated abscess. Treat underlying causes (bacterial infection, hypovitaminosis A).

- tracheitis

- Fungal, bacterial, parasitic, viral (Amazon Tracheitis Herpesvirus). tracheal wash and tracheal endoscopy are most useful. If acute dyspnoea, cannulate air sac. remove the obstruction by trachoscopy. Appropriate treatment, supportive care.

- parasites

- Trachea; Syngamus trachea. Air sac;Sternostoma tracheacolum. Ivermectin treatment.

Lower Respiratory Tract Diseases

- Air Sacculitis

- Bacterial or chlamydial aetiology most common. Also aspergillosis, mycoplasmas, canarypox, paramyxoviruses 1 and 5. Can be asymptomatic. Radiography and endoscopy for diagnosis.

- Air sac wash / biopsy most useful for accurate culture results. Parenteral antibiotics, nebulization, surgery for abscess, granuloma removal.

- Diagnosis: Radiography, culture, serology, faecal tests to differentiate cause. Laparoscopic examination of the air sacs following radiographic localization enables visualization of lesion plus direct culturing.

- Pneumonia

- Aspiration pneumonia in hand-fed birds. Granulomatous pneumonia is caused by mycoplasmas, fungi, bacterial (Pasteurella). Parenteral and nebulization therapy is required.

- Asthma/ Allergy

- Sneezing, wheezing, eosinophilia in the tracheal wash. No other diagnosis!! Rarely reported. Avoid allergen, use antihistamines, bronchodilators.

General Diseases

- Hypovitaminosis A

- Usually as a result of a seed-only diet. African Greys often present with clinical signs at 3-5years of age. Can be fatal. Squamous metaplasia with increased keratinisation of epithelia of the respiratory tract, GIT, renal tubules, etc. Initial signs include swelling and depigmentation of choanal papilla progressing to degeneration and abscessation of mucous glands. Compromised respiratory tract. Correct diet, add avian supplement (probably multiple deficiencies anyway). Parenteral vitamin A.

- Psittacosis

- Infection with Chlamydia psittaci; infects birds, cats, dogs, sheep. Difficult to diagnose – affected birds may have marked illness, lameness only, or appear clinically well. Latent infection possible – disease appears when stressed. The signs include; listless, dull, respiratory signs (respiratory distress, respiratory clicks, auscultation, air sac infection), enlarged liver and spleen on radiography, elevated white blood cell count (above 25 x109 per litre), especially if concurrent heterophilic left shift, conjunctivitis (ducks); turkeys and cockatiels – sinusitis.

- Aids to Diagnosis

- Cloacal swab, ELISA, PCR, serology.

- Post-mortem findings in in-contact birds – serous membranes thickened (air sacculitis, pericarditis), signs of septicemia in the carcass, enlarged spleen, liver (radiography, endoscopy, post-mortem), impression smear tests of parenchyma (liver, spleen, lung, kidney), and serosal (liver and spleen) surfaces with modified Ziehl-Nielson for elementary bodies.

- Zoonotic Implications of Psittacosis

- Warn owners of zoonotic risk, and make an informed decision about treatment or euthanasia. The symptoms in man are headache, fever, confusion, myalgia, non-productive cough, lymphadenopathy. The health status of the owner should be taken into account (e.g. HIV, immunosuppressive drug therapy). Adopt strict hygiene standards (wash hands with antiseptic after contact with bird, wear masks).

- Treatment

- It is advisable to include Psittacosis treatment if the disease is suspected, even if not diagnoses; treat under quarantine conditions, with plastic aprons, hats, masks, and gloves for staff.

- Parenteral:Doxycycline 2% (Vibravenos Steraject, Pfizer), 100mg/kg i.m. (half dose either side of the keel) and vitamin A injections. Treat with 45day course with injections on days 1,8,15,22,28,34,40,45. Repeat ELISA/PCR test (following stress/ prednisolone) a few weeks after treatment.

- Oral Dosing: Crush doxycycline (Ronaxan; RMB) tablets or ciprofloxacin (Ciproxin; Bayer) in lactulose.

- Aspergillosis

- Aspergillus fumigatus is the most common species. A. flavus and A.niger are less common. Chronic respiratory infection or peracute death. African Grey parrots, Blue-fronted Amazon parrots, and mynah birds are susceptible pet species. Goshawks, Gyrfalcons and penguins are also susceptible. As this organism is ubiquitous in the environment, birds generally succumb to infection only when compromised by certain factors. These include stress, malnutrition, age, antibiotic therapy, respiratory irritants, or concurrent disease. Both local and systemic, acute and chronic forms occur. Clinical findings in an affected bird include; emaciation, respiratory distress, neuromuscular disease, abnormal droppings, vocalization changes. The acute form is common in young or imported birds, severe dyspnoea, anorexia, and cyanosis (death). The chronic form is more common in the older captive birds, characterized by weight loss, intermittent dyspnoea (CNS Signs).

- Local forms include;

- Nasal aspergillosis – dry granuloma in one or both nostrils that causes erosion. Birds may present with one very large nares.

- Tracheal or syringeal – severe dyspnoea, whistling sounds as breath

- Air sac form – diagnosis based on endoscopy, radiography – focal granulomas or diffuse fungus seen

- Lung form – granulomatous pneumonia

- Systemic – thrombosis and infarction

- Diagnosis

- Hematology (see table), serology, radiography, endoscopy (trachea and air sacs), exploratory surgery. Fungal culture and cytology of sinus flush, the lung was air sac flush, air sac, and lung biopsy. (Haematology changes = leucocytosis, heterophilia, monocytosis, lymphopenia, non-regenerative anemia, hyperproteinaemia, hypergammaglobulinaemia).

- Treatment

- Surgical debridement and removal of plaques or granulomas if possible. Topical treatment with antifungal, nebulisation, oral therapy. Amphotericin B can be given intratracheally. Itraconazole is the oral therapy of choice due to its low toxicity and high efficacy (10mg/kg). Nebulisation with clotrimazole (‘Canesten’ in propylene glycol) for 15minutes daily in conjunction with oral itraconazole has been used successfully in a number of parrots by the author.

Further Reading

- Tully TN, Harrison GJ, 1994, Pneumonology, in ‘ Avian Medicine: Principles and Application‘, Ritchie, Harrison and Harrison (Eds), Winders Publishing Inc, pp556-581

- Murphy J, 1992, Avian Respiratory System. Proc. AAV 1992. Advanced Avian Seminars. pp398-411

- Tully TN, 1995 Avian Respiratory Diseases: A Clinical Overview, Journal of Avian Medicine and Surgery 93, pp162-174

Author Profile

Latest entries

Feeding Exotic BirdsDecember 29, 2025How to Switch or Convert Your Bird From Seeds to Pellets: Real-Life Case Studies and Practical Guidance

Feeding Exotic BirdsDecember 29, 2025How to Switch or Convert Your Bird From Seeds to Pellets: Real-Life Case Studies and Practical Guidance Feeding Exotic BirdsDecember 16, 2025A Practical, Budget-Smart Guide to Feeding Birds Well

Feeding Exotic BirdsDecember 16, 2025A Practical, Budget-Smart Guide to Feeding Birds Well Bird EnviornmentsDecember 7, 2025Understanding Budgie Cage Bar Orientation: Myths, Realities & Practical Solutions for Vertical-Bar Bird Cages

Bird EnviornmentsDecember 7, 2025Understanding Budgie Cage Bar Orientation: Myths, Realities & Practical Solutions for Vertical-Bar Bird Cages Feeding Exotic BirdsDecember 5, 2025How Dr. T.J. Lafeber Rewrote the Future of Pet Bird Nutrition

Feeding Exotic BirdsDecember 5, 2025How Dr. T.J. Lafeber Rewrote the Future of Pet Bird Nutrition